Vast amounts of planet-heating carbon dioxide are created during the manufacture of many key materials that support our lives – from paper to plastic. Our environment analyst Roger Harrabin has been exploring new low-carbon technologies which could help cut those emissions. He has enlisted artists to help him tell the story.

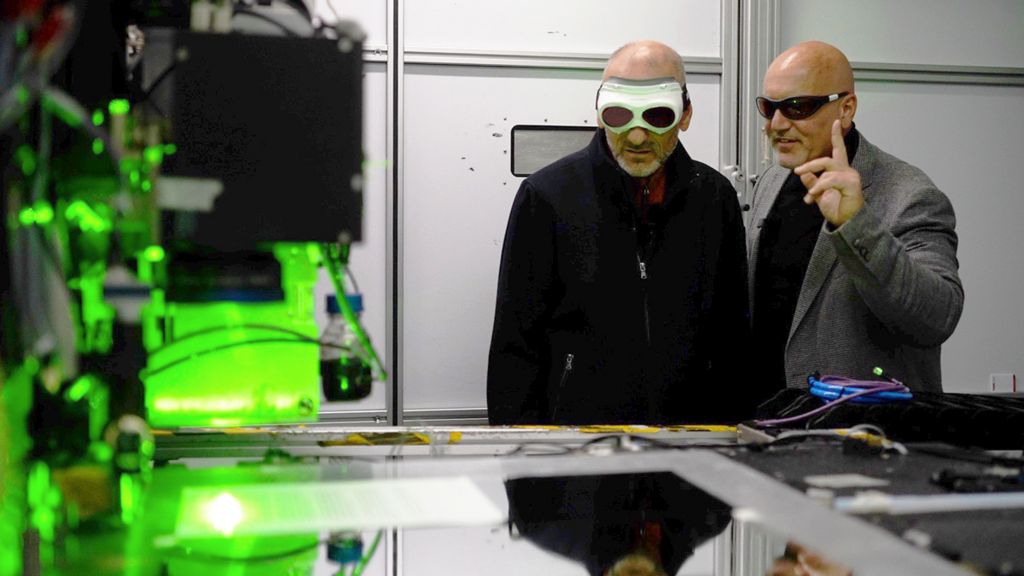

Scientists have invented a magical gadget that sucks the ink off printer paper so each sheet can be used 10 times over.

They aim to cut the amount of planet-heating carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the paper and pulp industry by reducing demand for office paper.

The trick to the so-called “de-printer” is specially coated paper, which stops ink soaking into the page. A powerful laser then vaporises the ink.

Lead developer, Barak Yekutiely from Reep Technologies in Israel, describes it as circular printing.

“If we care about the planet, we must stop cutting down so many trees,” he says.

The invention is featured in an iPlayer documentary on climate tech solutions. It’s called The Art of Cutting Carbon, and it’s my last film for the BBC after 35 years reporting the environment.

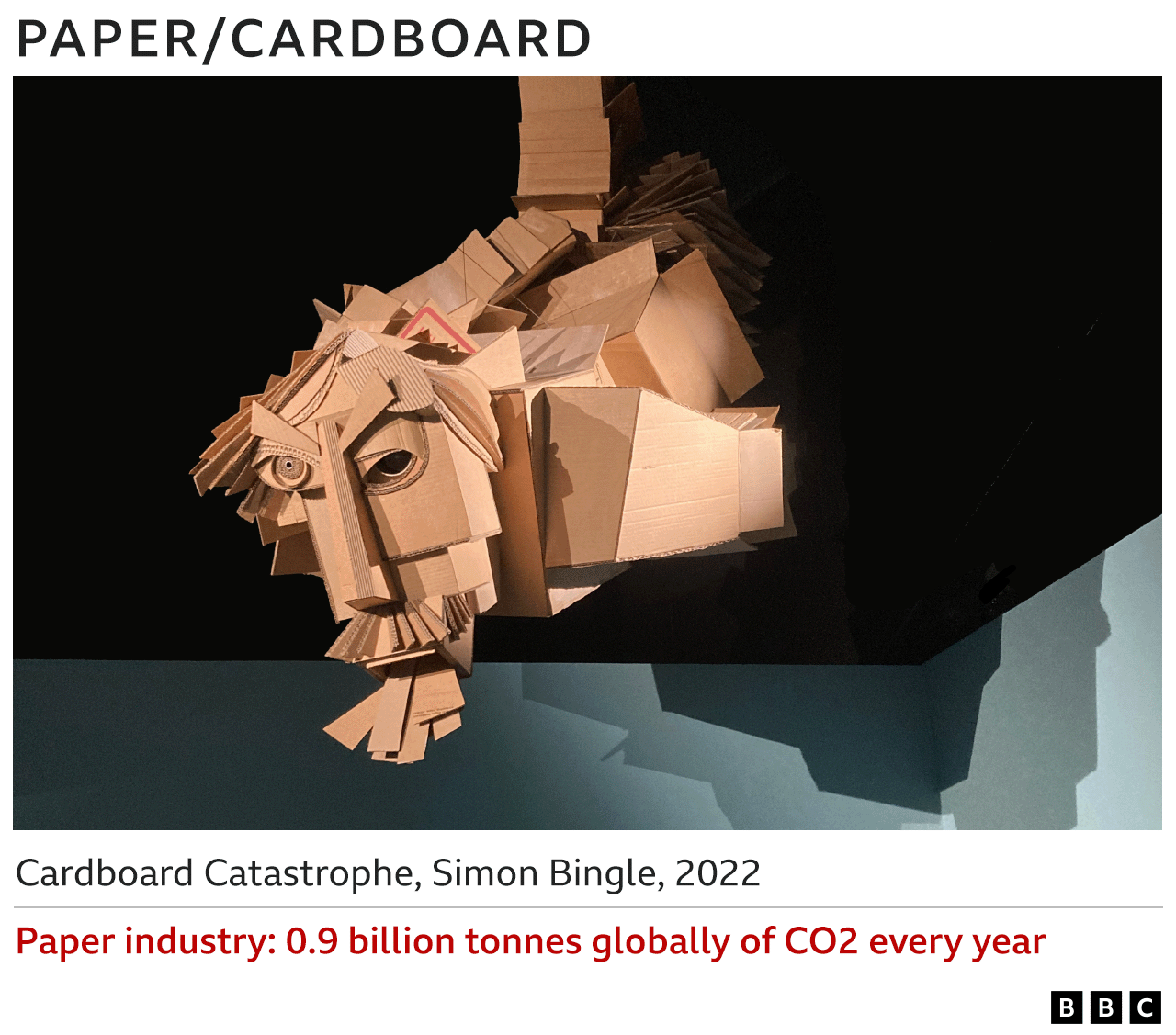

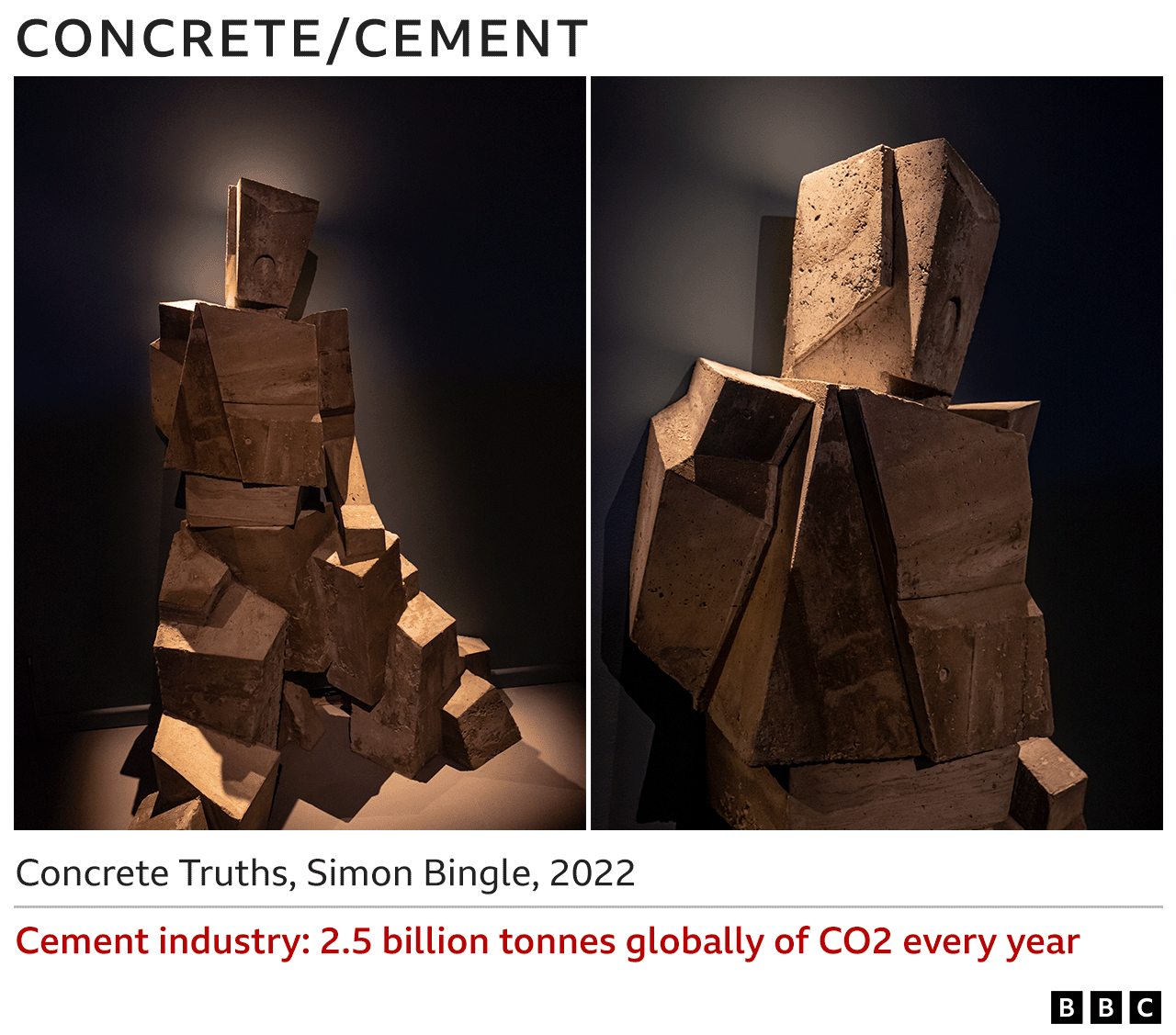

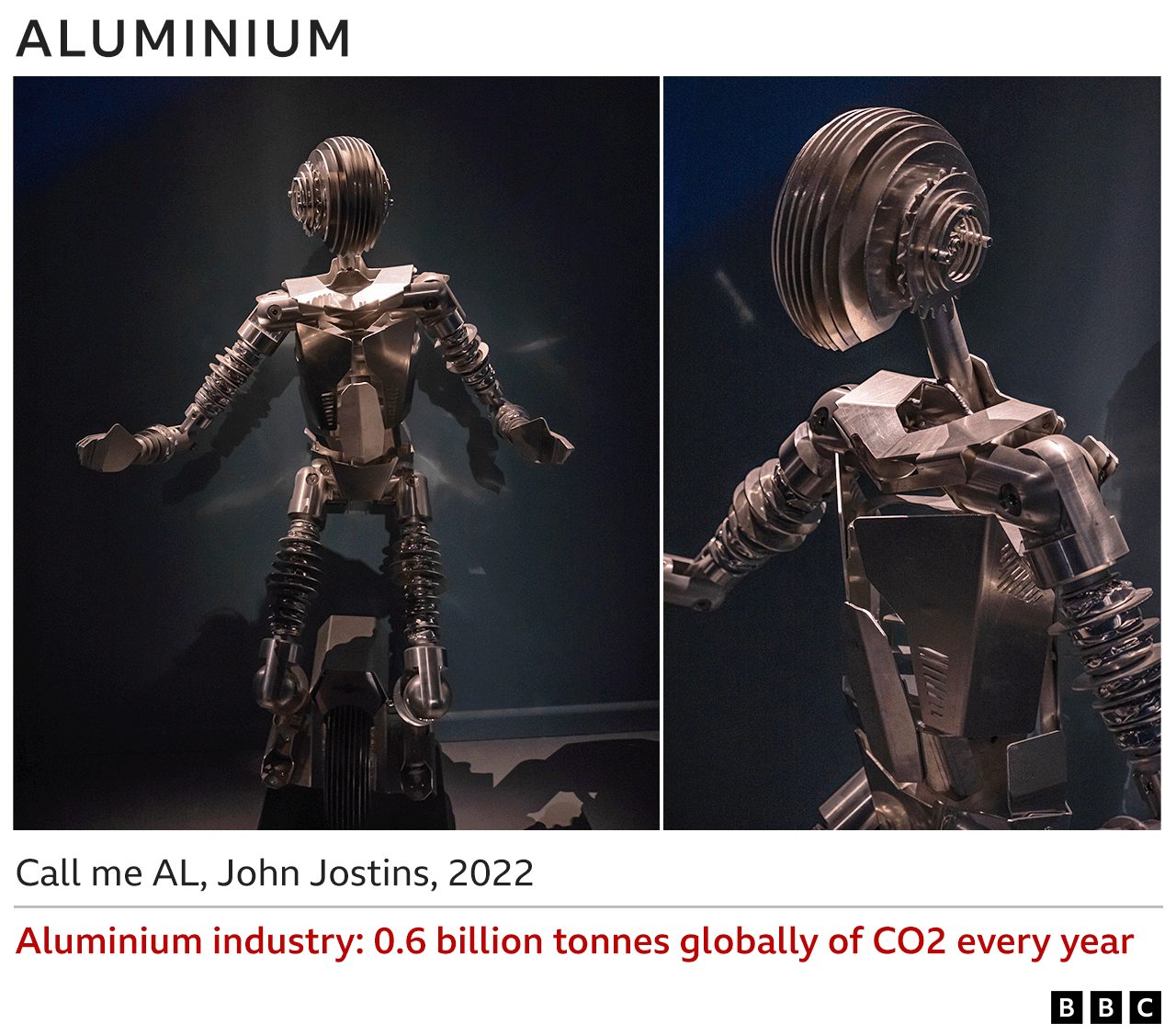

The film forms part of an exhibition at Cornwall’s Eden Project, where I have curated sculptures in steel, cement, plastic, aluminium and paper – to help me highlight the huge amounts of planet-heating CO2 produced globally from manufacturing these everyday materials.

Environment Analyst Roger Harrabin reports on the endeavours of British artists working with concrete, steel, aluminium, plastic and cardboard.

Experts say one way of tackling those emissions is to invent new technologies that limit the amount of CO2 produced. Another is simply to use less stuff.

The de-printer is part of an avalanche of innovation to produce technologies fit for the low-carbon age.

In northern Sweden, one company is a shining example of how to take CO2 out of steel manufacturing. Globally, the industry emits almost three billion tonnes of the gas a year – that’s roughly equal to all the annual CO2-producing activities in the entire Indian economy.

Normally, making steel involves mixing iron-bearing rock with coke – which derives from coal – then super-heating it at 1,500C, using highly-polluting coal or gas.

The heat sets off a chemical reaction that turns the iron into a precursor of steel. But this creates even more CO2 – in fact, the process makes more tonnes of CO2 than it makes steel.

But now, in the town of Lulea – just south of the Arctic Circle – the multinational steel manufacturer SSAB has found a way of stopping the creation of CO2.

The first step is to use renewable power – such as from wind turbines or hydro electricity – instead of coal to produce the necessary heat. Step two is to substitute hydrogen for coke in the reaction stage.

Instead of producing CO2 as a by-product, the reaction with hydrogen and iron produces only H2O… water.

Demand is high for the world’s first zero-carbon steel production – the steel makers are turning down new orders.

The cement industry produces 2.5 billion tonnes of CO2 a year. Cement is the main bonding ingredient for the concrete that forms the structures in our lives.

But making it involves heating limestone and that creates clouds of CO2. Harnessing coal or gas to provide the heat creates a double dose.

Now concrete makers are experimenting with other binding materials that don’t need to be cooked in the same way, and big players in the industry aim to be carbon neutral by 2050.

But we can’t wait that long to tackle climate change, so the rail firm HS2 is building a viaduct in Buckinghamshire in south-east England made from a sandwich of cement and steel.

This smart design allows less material to be used by harnessing the different physical properties of the cement and steel in a way that’s catching on fast. The engineers say this innovation cuts materials costs and halves the CO2 emissions that would have been seen in a more traditional construction.

HS2

Of course, taking a decision not to build the controversial HS2 route in the first place would have saved many more emissions.

And there’s a growing trend among engineers to try to squeeze more out of infrastructure that already exists, such as refurbishing buildings instead of knocking them down and using cement to build replacements.

The plastics industry is another of the top five CO2 offenders. Almost all the world’s plastic is derived from high-polluting oil and gas.

But in the Netherlands a bio-chemical firm Avantium is claiming a world first – a plant-based plastic to rival PET, (polyethylene terephthalate) which is used to make most drinks bottles.

The new product is called PEF (polyethylene furanoate) and is said to produce a third fewer emissions than PET.

The raw material is derived from wheat and corn. I’ve tasted it and it’s just like eating sugar.

There’s a frisson of excitement about this breakthrough.

But let’s face it, bioplastics are coming from a very low base. They account for about 1-2% of the plastics industry.

What’s more, competition for the land used to grow the raw materials for PEF bottles will increase as farmers try to feed people in a future world of deadly heatwaves.

The United Nations has promised a treaty to restrict the making of plastic – but governments are lagging behind the speed of climate change.

Aluminium is the last of our five main emitters – though it produces significantly less CO2 than cement or steel.

That’s partly because the energy needed to produce aluminium from bauxite rock is so huge that major firms have located where renewable power is plentiful and cheap, in places such as Iceland, with its energy from geothermal and hydropower.

The industry also says more than 95% of the aluminium produced is recycled because it’s so valuable. But even that requires high temperatures – so, in Dortmund, Germany, they’re resurrecting an invention that’s more than 100 years old.

It’s a machine that takes in aluminium chips, then warms them and compresses them though a sort of giant toothpaste nozzle, to produce a tube of re-formed aluminium – at a fraction of the emissions of normal recycling.

Wherever you look, innovations like this are helping firms reduce emissions. But here’s the trouble – the inventions are not being developed nearly fast enough to meet the global goal of almost halving CO2 by 2030.

The biggest problem for all these industries is the shortage of clean electricity from renewable sources to power factories as well as cars and our homes.

Prof Julian Allwood from St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, sums it up by saying: “So many of us would like to have a solution based on inventing a new technology. But unfortunately inventing it isn’t the problem.

“What matters is the speed at which we can scale things up. You can bring out a new phone and sell it very quickly but you can’t bring out a new power station quickly, so the solutions we need have to be fundamentally based on technologies that already exist – and about doing things differently.

“Because these materials [paper, steel, cement, plastic and aluminium] have been made in such high volumes – and have been so cheap – we’ve used them wastefully.”

Prof Allwood says he’s optimistic we can still calm climate change – but warns that in future we must find ways of using less material.