Tiffany Wertheimer

Tiffany WertheimerNasa has called off the launch of its big new Moon rocket – the Space Launch System (SLS).

Controllers struggled to get an engine on the 100m-tall vehicle cooled down to its correct operating temperature.

They had previously worried about what appeared to be a crack high up on the rocket but eventually determined it was merely frost build-up.

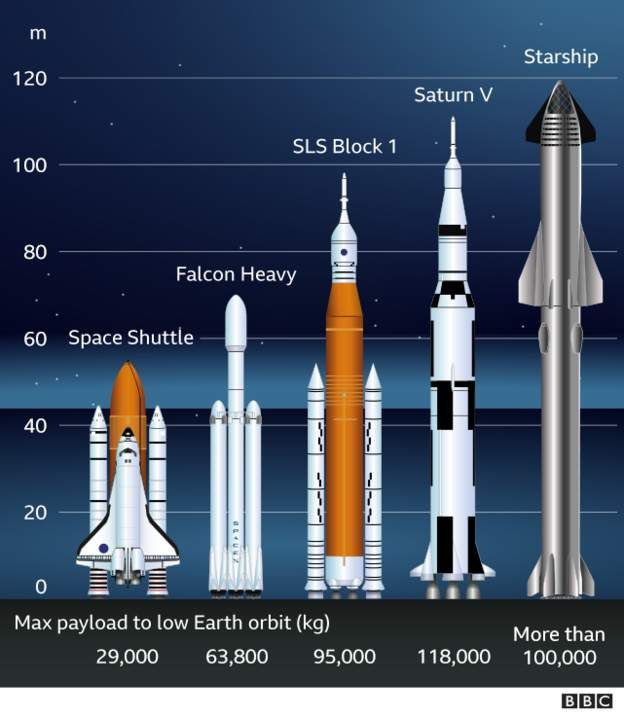

The SLS is the biggest rocket ever developed by Nasa. It will be used to send astronauts back to the Moon.

The maiden flight, part of Nasa’s Artemis programme, is just a demonstration with no one onboard. But ever more complex missions are planned for the future that will see people live on the lunar surface for weeks at a time.

Nasa has the option to try again on Friday, if the engine issue can be resolved by then.

But it’s possible the rocket may have to be rolled back to the assembly building at the Kennedy Space Center for more extensive work, which would delay the flight to September.

Weather also plays a part in whether a launch can go ahead – and while Nasa has several opportunities over the next week to fly the SLS, the weather here in Florida is very dynamic at this time of year.

Electrical storms frequently pass over the spaceport – indeed the pad’s lightning towers have been struck several times in recent days.

The launch of #Artemis I is no longer happening today as teams work through an issue with an engine bleed. Teams will continue to gather data, and we will keep you posted on the timing of the next launch attempt. https://t.co/tQ0lp6Ruhv pic.twitter.com/u6Uiim2mom

— NASA (@NASA) August 29, 2022

Hundreds of thousands of people had travelled to Cape Canaveral hoping to see the launch. Pictures showed thousands of cars parked on the side of a highway, prompting traffic warnings.

When it eventually takes off, the rocket’s job will be to propel a test capsule, called Orion, far from the Earth.

This spacecraft will loop around the Moon on a big arc before returning home to a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean six weeks later.

Orion will be uncrewed for the first mission, but – assuming all the hardware works as it should – astronauts will climb aboard for a future series of missions, starting in 2024.

The mission’s chief objective actually comes right at the end.

Engineers are most concerned to see that Orion’s heatshield will cope with the extreme temperatures it will encounter on re-entry to Earth’s atmosphere.

Orion will be coming in very fast – at 38,000km/h (24,000mph), or 32 times the speed of sound.

“Even the reinforced carbon-carbon that protected the shuttle was only good for around 3,000F (1,600C),” said Mike Hawes, the Orion programme manager at aerospace manufacturer Lockheed Martin.

“Now, we’re coming in at more than 4,000F (2,200C). We’ve gone back to the Apollo ablative material called Avcoat. It’s in blocks with a gap filler, and testing that is a high priority.”

The European Space Agency has provided the service module for Orion. This is the rear section that pushes the capsule through space. It’s an in-kind contribution that Europe hopes will lead to its nationals being included in future journeys to the surface of the Moon.

Several missions are being planned – currently it’s up to Artemis IX.

By that stage there should be habitats and roving vehicles on the Moon for astronauts to use.

But ultimately, Artemis is seen as a proving ground to get people to Mars.

“The timetable for that was set by President Obama. He said 2033,” recalled Nasa Administrator Bill Nelson.

“Each successive administration has supported the programme and the realistic timeframe that I’m now informed is the late 2030s, maybe 2040.”