A Soldati

A SoldatiWild chimpanzees have their own “signature drumming style” according to scientists.

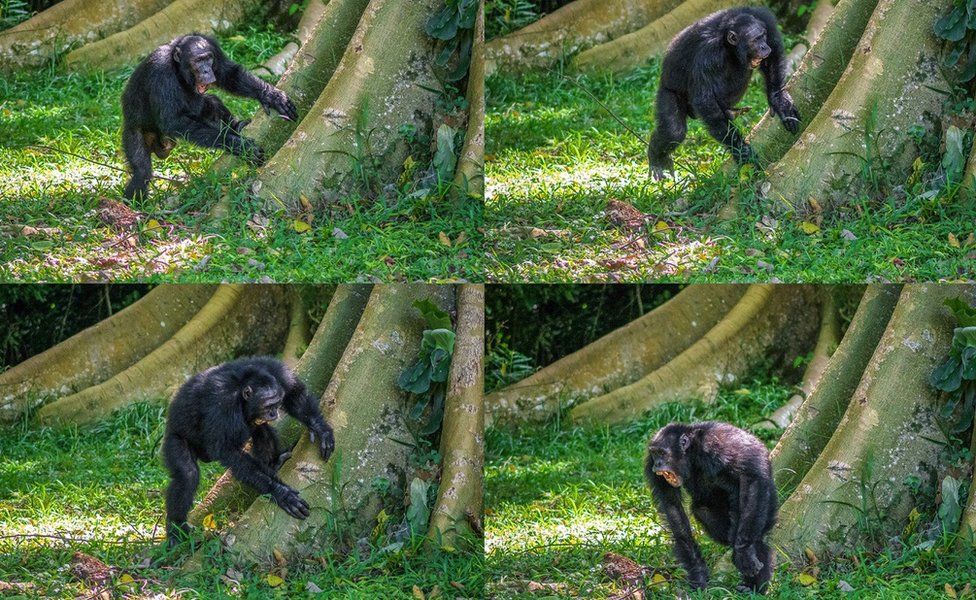

Researchers who followed and studied chimps in the Ugandan rainforest found that the animals drum out messages to one another on tree roots.

The scientists say that the signature rhythms allow them to send information over long distances, revealing who is where, and what they are doing.

The findings are published in the journal Animal Behaviour.

Dr Catherine Hobaiter from the University of St Andrews explained that the wild apes use huge tree roots as a large wooden surface to drum on with their hands and feet.

“If you hit the roots really hard, it resonates and makes this big deep, booming sound that travels through the forest,” she told BBC Radio 4’s Inside Science programme.

“We could often recognise who was drumming when we heard them; it was a fantastic way to find the different chimpanzees we were looking for. So if we could do it, we were sure they could too.”

Each male chimpanzee, the scientists found, uses a distinct pattern of beats. They combine it with with long-distance vocalisations, called pant-hoots. And different animals drum at different points in their call.

Lead researcher on this study, PhD student Vesta Eleuteri from the University of Vienna, described how some individuals have a more regular rhythm, like rock and blues drummers, while some have more variable rhythms, like jazz.

“I was surprised that I was able to recognise who was drumming after just a few weeks in the forest,” she said. “But their drumming rhythms are so distinctive that it’s easy to pick up on them.”

Ms Eleuteri described one young male chimp, that researchers have named Tristan, as “the John Bonham (late Led Zeppelin drummer) of the forest”.

“He makes these very long drumming bouts with lots of beats and you can tell them from far away, so you can just tell it’s Tristan drumming.”

The animals also appeared only to use their signature rhythm when they were travelling. The researchers speculate that a chimp chooses whether or not to give his identity away.

“If you’re showing off to a group around you – if you’re displaying – you might not necessarily want the big alpha male who’s around the corner to know who you are,” said Dr Hobaiter. “You don’t want to give the game away.”

She added that understanding chimps’ drumming in this way could solve a longstanding communication puzzle: wild chimpanzees greet each other when they meet, but they do not seem to “say goodbye” when they split off in the forest.

“The chimps might not need to say goodbye, because they’re effectively able to keep in touch while they’re away,” Dr Hobaiter explained.

“These long distance signals give the chimps a way to check in with one another. That might help us to understand one of these things that we thought was a real difference between chimps and humans, and help us to understand why that difference might have come about.”