Getty Images

Getty ImagesA promise from the developed world to foot more of the climate bill has raised fresh hopes of breakthrough at the UN climate summit COP27.

Nations meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, are frantically trying to find agreement as the talks are extended into the weekend.

The European Union has suggested a new fund to help poor nations deal with climate disaster.

Developing nations insist they will push for the best deal on the table.

The summit is nearing its end after two weeks of talks to make progress on tackling climate change, but there were fears it could collapse over the question of money. It was supposed to finish on Friday and is now expected to go on until at least Saturday.

Vulnerable nations including Pakistan, which leads developing countries here, say richer nations owe this money because they historically released most of the greenhouse gases that cause global warming.

The devastating floods in Pakistan this summer, which killed about 1,700 people, have been a powerful backdrop to talks in Egypt.

But rich nations are worried about signing a blank cheque. At the start of the summit, the US was adamant there would be no new fund, and it has been silent in negotiations, observers say.

In a possible breakthrough on Friday morning, the European Union proposed a special fund that would be funded by a “broad donor base”.

That suggests that China, a country which now emits large amounts of greenhouse gases (those gases that warm the atmosphere), could contribute too.

China is usually in the same group as developing nations, and historically contributed little to global warming. But this fund could call on them to help pay the bill.

“We are gratified that overnight there has been a major breakthrough from the EU… focussing particularly on most vulnerable countries,” Tuvalu Minister of Finance Seve Paeniu told BBC News. He represents one of the low-lying island nations most at risk from climate change.

“It’s great to see some leadership finally, but we’ll see what we get out of this,” Nisha Krishnan from the World Resources Institute told BBC News.

The EU’s proposal “comes with strings attached” and it is not supported by all developing nations, says Prof Michael Wilkins at Imperial College Business School in London.

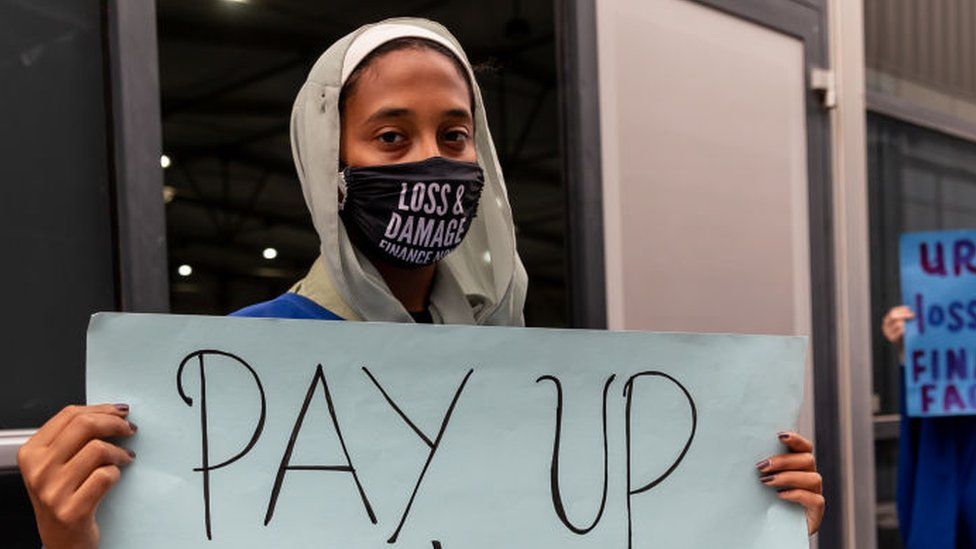

The question of this money, known as loss and damage, has dominated COP27. Nations at severe risk from climate disaster were pleased to get it on the agenda, after 30 years of trying.

The deal is not yet over the line.

Talking about the funding, Ms Krishnan said “this is the biggest thing that could make or break this conversation”.

It will be important to see what the US does as well as China, she suggests.

Outside of the negotiation rooms, NGOs and activists continue to call for much stronger promises from COP27.

“The bare minimum is do something to prepare the upcoming generation. You cannot just leave us hanging. This is essential for Africa,” said Mohammed Sherif, a 17-year-old activist from Egypt, saying that nations must lower greenhouse gas emissions and help countries adapt.