Danny Lawson/ PA Wire

Danny Lawson/ PA WireFracking can go ahead in England, the government said on Thursday, lifting a ban on the controversial process.

A moratorium was put in place in 2019 following concerns over earth tremors.

But with the energy crisis worsening globally and world leaders scrambling to secure energy supplies, the question has been reopened.

The decision comes alongside the publication of a new scientific review into the practice by the British Geological Survey (BGS).

The BGS has concluded there is still a limited understanding of the impacts of such drilling – a way of mining gas and oil from shale rock.

“In light of (Russian President Vladimir) Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine and weaponisation of energy, strengthening our energy security is an absolute priority”, Business and Energy Secretary Jacob Rees-Mogg said in a statement announcing the end of the ban.

Fracking in the UK has been a controversial subject within local communities and amongst MPs due to its association with minor earthquakes.

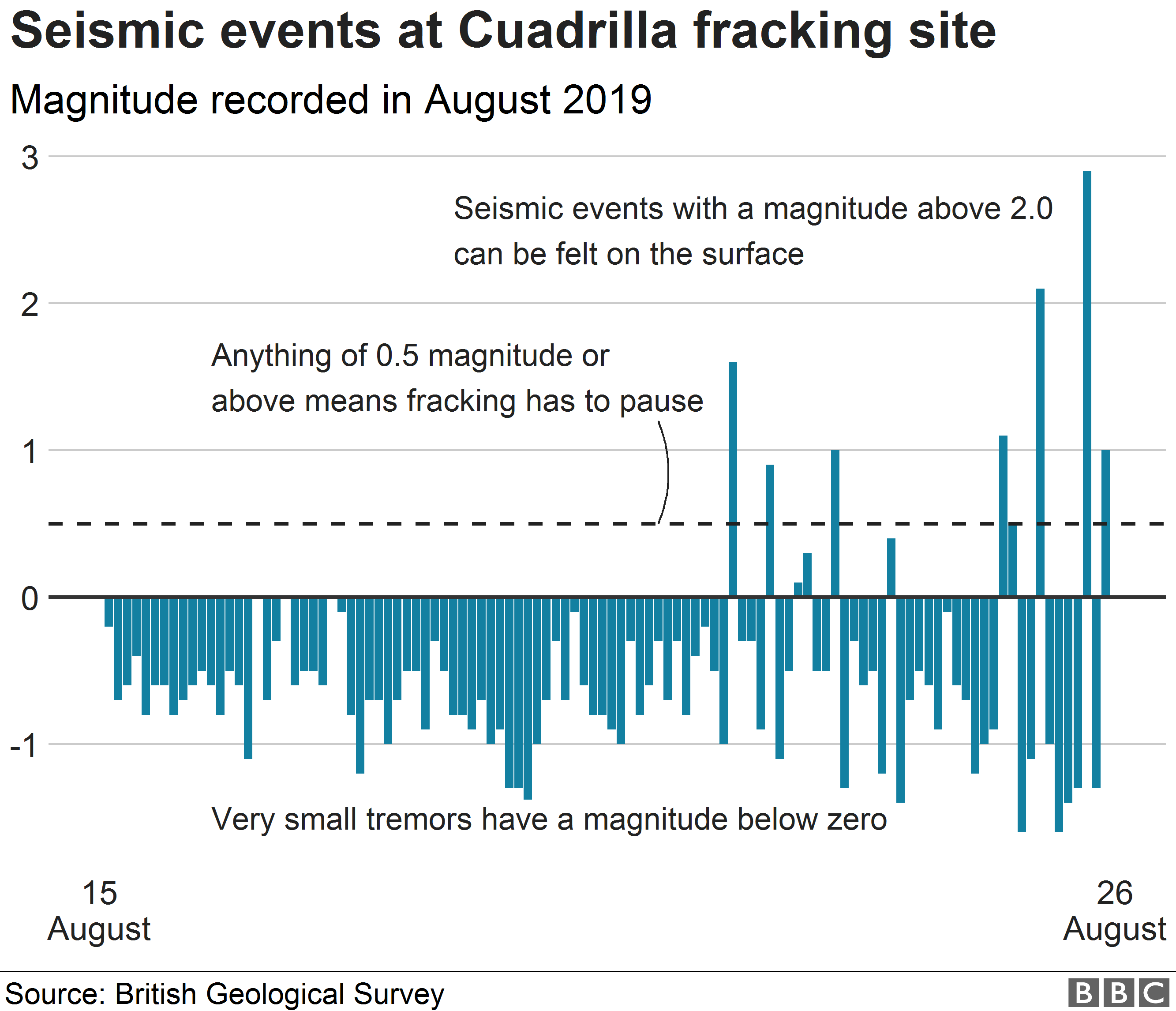

In 2019, at oil and gas exploration company Cuadrilla’s fracking site in Lancashire, more than 120 tremors were recorded – although most were too small to be felt.

Alongside the announcement on Thursday the government published a new review, commissioned in April, from the British Geological Survey (BGS) which considers any changes to the science around the practice.

On the risk of larger tremors from fracking the report concludes: “Forecasting the occurrence of large earthquakes… remains a scientific challenge for the geoscience community.”

Within shale rock there can be small faults and areas of stress. During drilling, water is injected into the rock to extract the gas. The water lubricates the shale rock, moving parts of the rock along these faults. This movement can trigger a tremor.

The BGS points out that although there has been progress in identifying these faults there is limited exploration and therefore “it is not possible to identify all faults that could host earthquakes with magnitudes of up to 3…even with the best available data”.

“The BGS report indicates that in terms of the science, little has changed since the 2019 moratorium on fracking,” said Honorary Professor Andrew Aplin, at Durham University Earth Sciences Department. He was not involved in the review.

This worries campaigners and locals who fought to stop the practice.

“Ripping up the rules that protect people from fracking would send shockwaves through local communities,” said Friends of the Earth energy campaigner Danny Gross.

“This announcement suggests that the government is planning to throw communities under the bus by forcing them to accept ‘a higher degree of risk and disturbance.”

But Rees-Mogg said in his statement that: “tolerating a higher degree of risk and disturbance appears to us (the government) to be in the national interest given the circumstances.”

The House of Commons on Thursday saw heated debate on the issue between Rees-Mogg and Labour’s shadow climate change secretary Ed Miliband.

Rees-Mogg said it was “important” to use all available sources of fuel within the UK rather than import them.

But Milliband said this would not lower energy costs and reminded Mr Rees-Mogg of a 2019 Tory manifesto pledge not to support fracking unless it could be done safely.

Some of the criticisms of fracking don’t make much sense.

Critics say chasing the methane trapped in ancient shale rocks will prove too difficult and expensive to ever be profitable.

That is no reason to keep the moratorium. Companies should be free to decide whether they think it is worth doing or not.

Or how about the claim local communities will never allow it? Surely, they should decide.

The important question is whether we need this new source of fossil fuels at all.

We know any additional carbon dioxide in the atmosphere adds to the problem of climate change.

What is more, fracking won’t affect the price you pay for your energy.

That’s because the frackers – just like the oil and gas companies in the North Sea – will sell whatever gas they produce to the highest bidder, as INEOS made clear when I spoke to the company last week.

Companies involved in fracking including Cuadrilla welcomed the lifting of the ban. Cuadrilla Chief Executive Officer Francis Egan told the BBC News Channel that the first gas could be flowing in six months, although that would depend on local planning approvals.

Even with the reversal of the ban, permit arrangements still remain very strict.

Currently if there is any seismic activity at fracking sites companies have to proceed with caution. And they have to pause activity altogether if there is a tremor over 0.5 magnitude.

The BGS says that earthquakes can only be felt at a measurement of 2.0 – which is thirty times stronger than this.

Chris Hopkinson, chief executive officer for UK gas and oil exploration company IGas Energy, told BBC’s Newsnight programme earlier this week that this was a lot stricter than the requirements for other sectors, saying: “We just want to play on a level playing field.”

Rees-Mogg told Newsnight on Wednesday night that the level of seismic activity would be reviewed, but said it was too early to confirm what that new level would be.

The Scottish and Welsh governments continue to oppose fracking, and say they will not use their powers to grant drilling licences.