Getty Images

Getty ImagesFrom all the pictures of parched fields, dusty soil and dried-up reservoirs, it might appear obvious there’s a drought.

But from a scientific point of view, it’s more complicated than that.

There’s no one definition of drought – it’s different depending on whether you look at weather, agriculture or water flow in rivers and streams.

And when it comes to declaring an “official” drought, government agencies look at how the long dry spell is affecting food production, water supplies and the environment.

That includes how much rivers and streams are shrinking, which puts wildlife and water supplies at risk. They also look at threats to crops and livestock if fields are turned into dust bowls.

How water supply is affected

One big indicator for drought is hydrology – the flow of water through rivers and the state of the water stored underground in permeable rocks beneath the soil.

These are crucial for supplying the drinking water that reaches our taps.

Rivers are running at exceptionally low levels in much of southern England and Wales, including the River Yscir, Colne and Wye. There are reports of streams drying up and rivers shifting downstream.

The amount of water stored in aquifers – the layer of spongy rock that soaks up water – is below normal for this time of the year.

Reservoirs are also running empty. At the end of July reservoirs were at their lowest levels in England and Wales since records began in 1990, according to the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology.

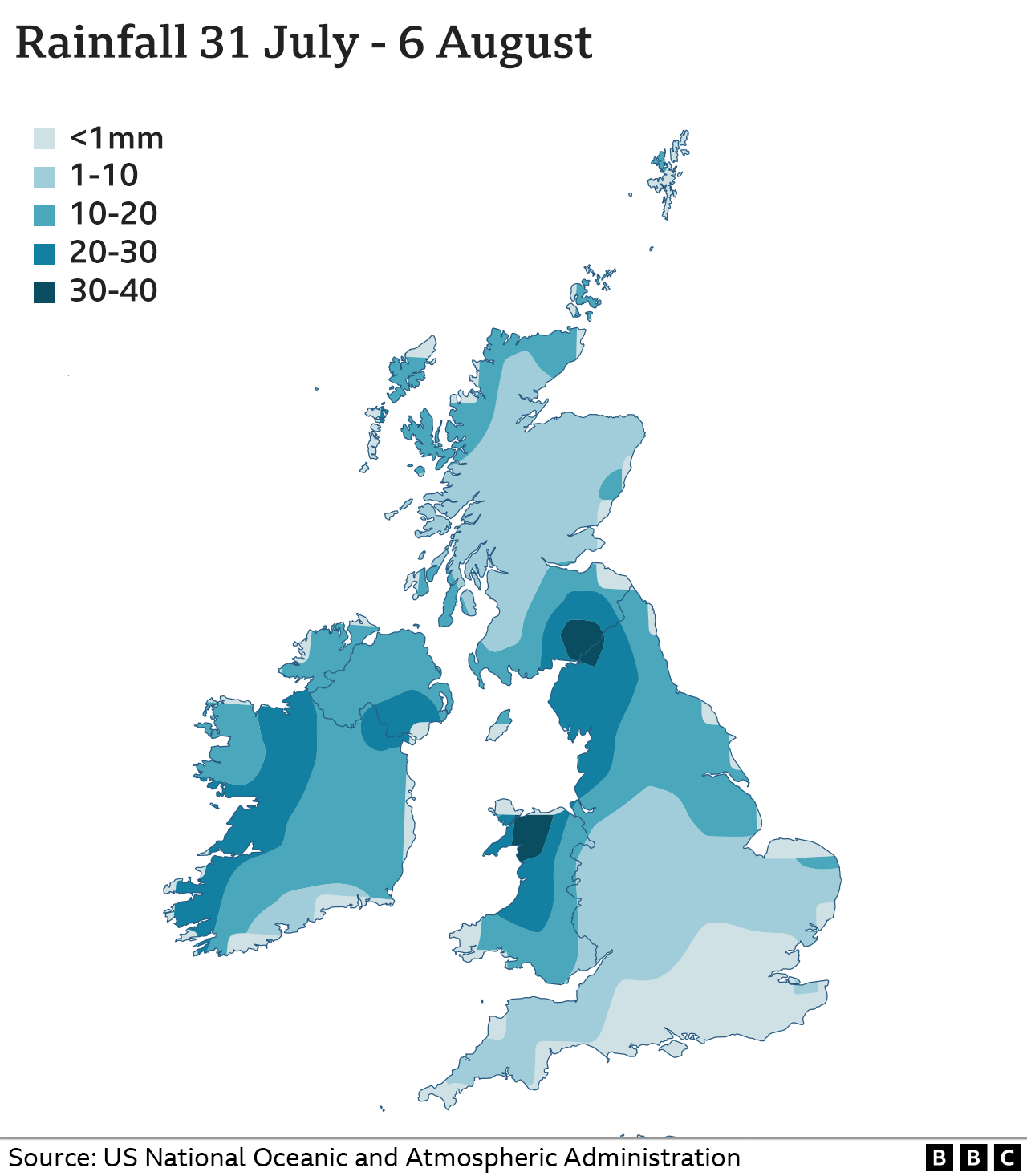

A north-south divide

But it should be noted that there’s something of a north-south divide. Because of the UK’s geological make-up and the influence of weather patterns, some parts of northern England and Scotland are escaping the worst of the parched conditions.

Rivers in the north are generally at higher levels and also respond much more quickly when rain falls.

That said, the drought in much of southern England and parts of Wales is likely to persist for some time. Even if it does rain, it’ll take a long time for river levels to fill up enough to return to normal flows.

How drought affects food and wildlife

Experts warn the extreme weather will likely lead to smaller harvests, which will make the food we buy in the supermarkets even more expensive.

Scientists will be monitoring the impacts of the drought on wildlife. As water courses dry up or run low, habitats for fish and invertebrates start to shrink, with knock-on effects for animals higher up the food chain.

And pollutants in rivers become more concentrated, amplifying their impact on wildlife.

How climate is linked to drought

Experts will also be looking at the wider question of the links between heatwaves, drought and climate change.

The UK has experienced regular periods of drought in the past, including the last official drought in 2018-19. And to a certain extent, drought is normal and part of natural weather cycles across the world.

But dry conditions are also expected to become more frequent and intense as Earth moves beyond the 1.2°C of climate change we have seen to date.

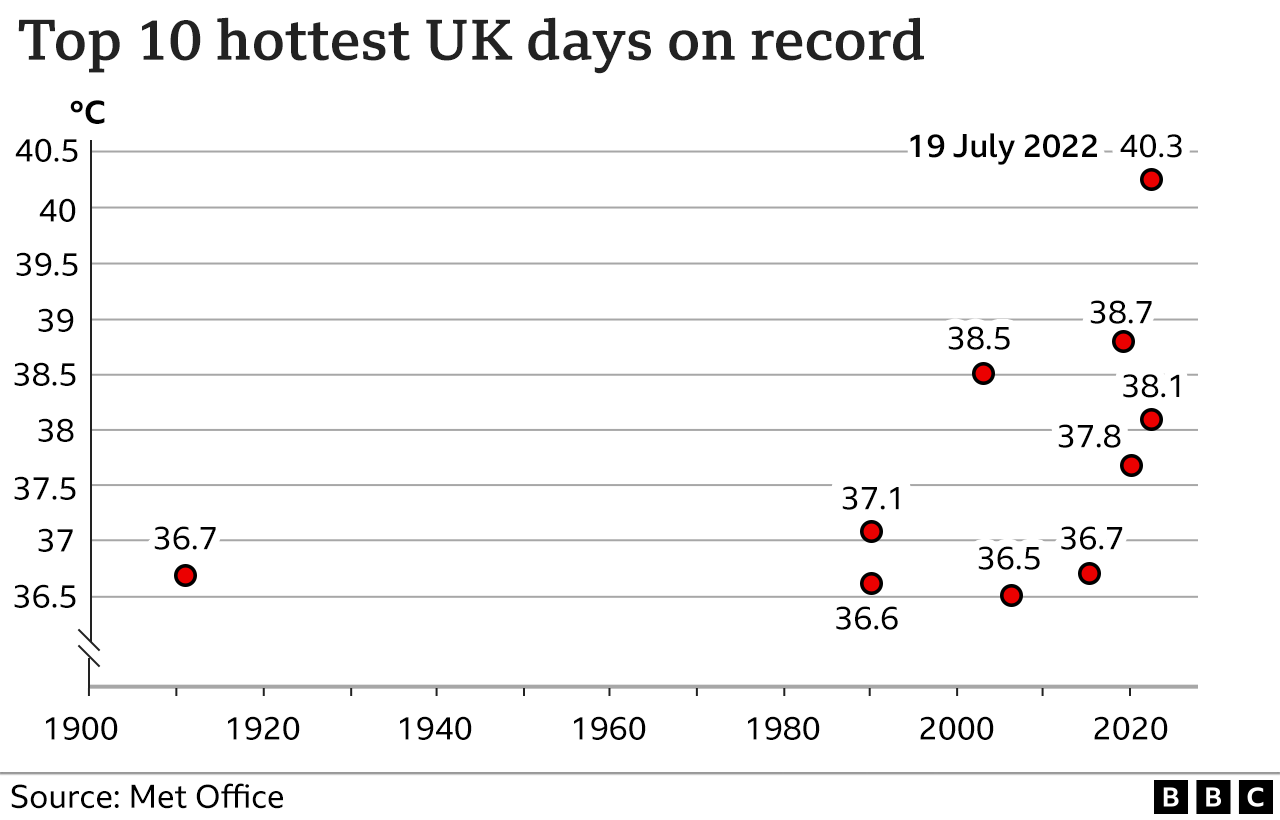

The ten warmest years on record in the UK have occurred in the 21st century, with data stretching back to 1884.

Climate scientists say that the UK’s extreme heat in July would have been “almost impossible” without human-induced climate change.

July was the driest in England since 1935, with many areas seeing far less rainfall than average.

The latest set of simulations for the UK project hotter and drier summers, plus warmer and wetter winters, with larger changes in summer compared to winter rainfall.

That means water companies and farmers will have to plan how to harvest and store rain in winter to address shortages in the summer.

Follow Helen on Twitter @hbriggs.